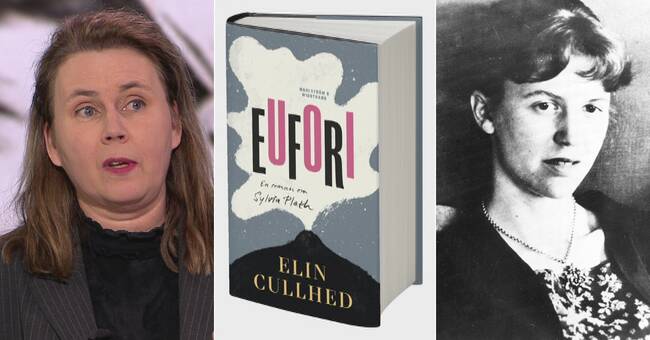

Elin Cullhed's debut in 2016, the youth novel The Gods, was part of a strong narrative wave about how girls are made into women, where Tove Folkesson's "Kalmar's hunters" is one of the standard.

The gods were infernally skilled, it described intoxication, "I felt like a church must feel", and captured a spirit of the times where Swedes say "well done": "It's like Swedish for love".

Next year will be

90 years since the author Sylvia Plath was born.

But since we can not imagine her as an aging lady, the story of her death always recurs.

A few weeks ago it was 58 years since she gave up and put her head in the oven after turning on the gas.

The tape around the children's door, the note on their pram, what would become the legendary collection of poems Ariel in a black folder on the desk.

But sorry - all that Elin Cullhed ignores - she instead goes straight into the story of Sylvia Plath, from within herself in this fictional novel fantasy about an icon.

She makes her a contemporary, without it feeling compulsive, perhaps to a writing sister.

Cullhed lets Plath's

pictures color the text - here they are still just material in the making - but at the same time she writes out a woman's figure and stubbornness with prose.

It is as choppy and comma-braked, rhythmic and not flowing as in irresistible, but as in the style of breathing.

And it describes a rather troublesome woman: also both boundless, condescending and arrogant.

The novel begins shortly before the end, with a list of seven reasons not to die.

It starts with the children's skin and ends with their names in two separate entries, desperate reasons without arguments.

Then the novel starts again with a key sentence.

"It was my life that was the text."

Because that is how she has read,

as female poets often get their work read with their lives as the key and conclusion, and so research and worship have approached Plath.

As if her experiences spilled out poems about what happened on pure automaticity, just as breast milk here becomes language, into mother tongue.

If you try to understand the authorship before the icon Plath was born, while she was struggling to find her speech, you end up in Cullhed's universe, where everything is just going - the children are so small, her only novel The Glass Dome - for decades read as the text of her life - only during release.

Everything remains.

It's euphoria, next door to darkness.

Euphoria is her joy of life, her longing and desire.

The glitter of life, all she should dampen and discipline, which goes out in the abandonment when her husband the poet Ted Hughes, easily offended and solitary but also a modern man for his time, leaves their lives.

The novel's weakness is the over-emphasized modern dialogue between Plath and Hughes, and that the time in which this takes place, a cold, feared post-war period, is barely hinted at behind all the daffodils.

But it is the daffodils that are the light, the dream of a normality where you have neighbors, a body, a bank account, a car.

When freedom and security do not kill each other.

Elin Cullhed has written a happy novel.