Walter Benjamin believed that he had discovered in the cinema an art, an act, that ended with the removal of the sacred. The holy is always imposed, the profane is given. In its thoughtless way of ending rituals and aura as symbols of privilege, cinema is so close to the world that it can transform it. That absent-minded gaze that, according to the Jewish philosopher, defines cinema viewers allows the possibility of associations of ideas, of active discussion, of chance, of error, of revolution perhaps. 'Le regard de Charles' ( Charles's gaze) is perhaps the strangest and brightest 'Benjaminian' film. It has the 'golden' charm, almost sacred and undoubtedly mythical, of its true author, Charles Aznavour,and yet it has nothing to do with him. He just watches. It is a look as excited as it is distracted from the world; one more, any one, and yet completely unique and transformative. Revolutionary.

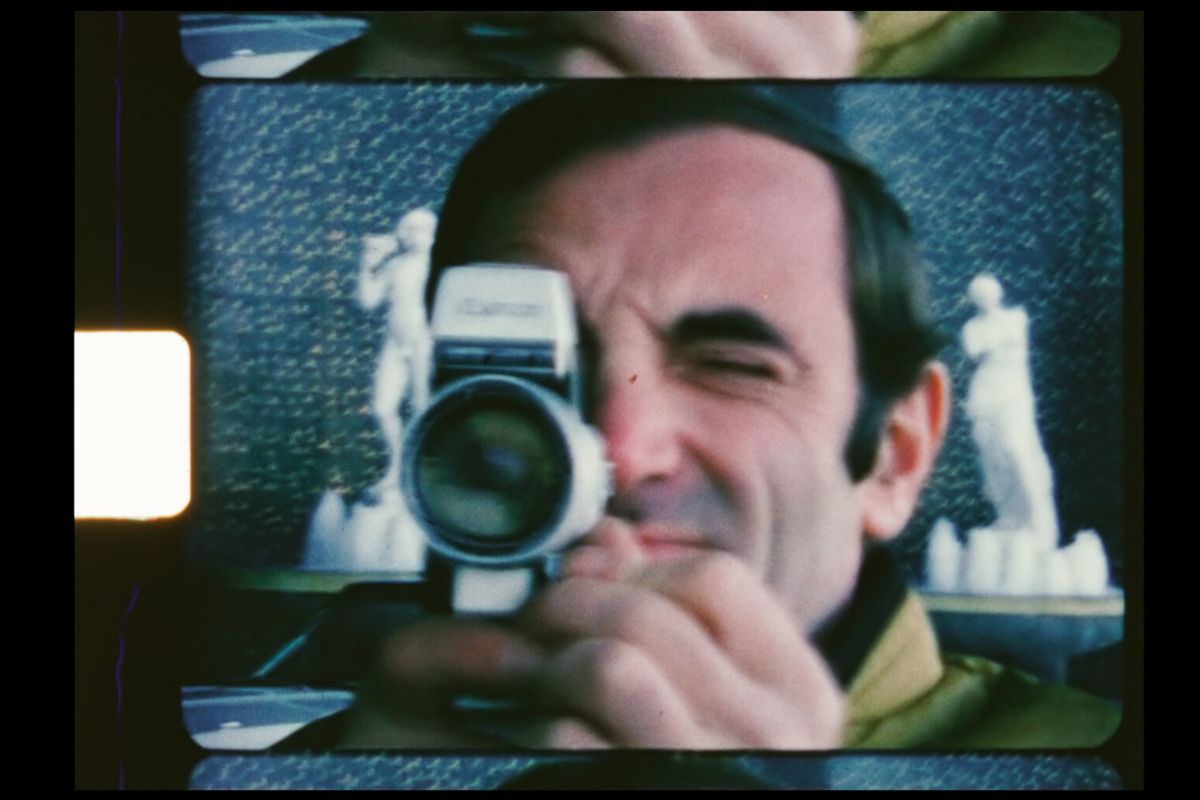

'Le regard de Charles', to put us, is not exactly a fiction. Neither is a documentary. The direction is signed by Marc Di Domenico because he is in charge of cleaning up, ordering and giving meaning to the original material. "I came to Charles," says the director by telephone, "through his son Mischa. After meeting us, I began working with him on an interview-report for French television. One day he showed me the box in which he kept all the tapes that he had shot throughout his life since Edith Piaf gave him a Bolex camera back in the late 1940s. I do it in every interview like this, but I find it hard to describe the emotion I felt. It was a whole life of Charles , but without Charles. " And it is there, in the contradiction, where the miracle lives.

Indeed, the singer of Armenian origin who was also an actor and who above all and above all was small, ugly, perfectionist, irascible, irresistible and sentimental , dedicated himself to recording not so much what he saw or felt as his own gaze. The body and soul of the camera operator that he was is transformed and comes alive in everything he shoots, in everything he sees. The first images have a rare ethnographic air. What he discovers in Morocco or the Congo surprises and excites him. And so what it offers the viewer is as surprising as it is exciting. "It attracts attention," observes Di Domenico, "as his beginner images have something impulsive, anxious. They vibrate at the same rate that I imagine he did when he saw himself with a camera in his hands. But as he gets used to it and he makes of the camera an extension of himself (he went with her to all sides), the image is serene, acquires depth and even becomes a psychological portrait of himself ". And so it is.

From a banal point of view, the film is an invitation to enter in a completely different way into the intimate life of the star, her obsessions, her fears and, of course, her loves. The artifice mounted by Di Domenico consists of reciting the actor Romain Duris excerpts from texts, letters and reflections of Aznavour himself on the filming by dumb force. And in this way, we see Aznavour go hungry in Montmatre when he dreamed of being an artist. And we see him suffer with his grandmother when, after so many years, he comes to visit her in his dream Armenia. And we see him fall in love first with Evelyne Plessis with whom he traveled by boat to conquer New York and with the transparent Swedish Ulla Thorsell later. With the latter we even attended their wedding in Las Vegas with Kirk Douglas and Sammy Davies Jr. More than a family album, they are the same eyes of one of the most peculiar voices that the ' chanson ' has given . Later, Charles and his camera also mourn the death of their son Patrick at the age of 25, an overdose. Celluloid is also a wound.

But with everything, what counts is just what you can barely see; the opposite of everything. Account the voice in 'off' that Aznavour filmed and now. He never bothered to review, mount or return to the filmed. What kept him focused on the camera was the very power to zoom in and transform reality. The world loses its sacred imposture, its aura that Benjamin would say, to acquire the profane touch of the substantial, the unique, the true. And that is what 'Le regard de Charles' offers ; the possibility not so much of getting closer to Charles as to everything that made Charles that man before the myth that he was. And it is. We are talking about the man who wrote 800 songs with great pain ("He knew a lot. He suffered," recalls Di Domenico); of the man who wanted to be an actor first of all; of the man who starred in films like ' A taxi for Tobruk' or ' Pull over the pianist ' (" Truffaut told him that the film was nothing but his gaze"); of the man who acted until almost the same day of his death at 94 years old in 2018 and who sang 'J'abdiquerai' until he almost died ... "He managed to see ten minutes of the final assembly before dying," says the director. . "And he likes me". It is not so much film as revolution. It is cinema without the imposture of cinema. It is reality transformed by a gaze, the gaze of Charles Aznavour.

According to the criteria of The Trust Project

Know more- movies

- culture

CultureLeonardo DiCaprio and Robert De Niro auction to participate in the filming of Scorsese to raise funds against the coronavirus

CinemaThe Cannes Film Festival neither cancels nor the opposite

The final interview Mario Casas: "There are more prejudices against Spanish cinema in our country than outside it"