Edward Estlin Cummings felt death very closely in a Great War with no capitals or epic teeth. His survival poem did not consist of another goodbye to arms as an ambulance driver under the Austrian shells, but rather a mass of human trenches and intimate labyrinths on the walls of La Ferté-Macé, a prison in Normandy for allegedly stripped spies of any presumption of innocence.

His case was very different from that of Ernest Hemingway, who was five years younger and, as always since then, threw more fearless literature than anyone: enrolled in the body of Red Cross ambulance drivers, the summer of 1918 He volunteered to go to Fossalta, next to the Piave River, north of Venice, with Austrian troops howling with his mortar fire, and the rest is already a legend of the lunar night, bloody thighs, courage medals and nurses consecrated to heat of life

Edward Estlin Cummings -EE Cummings definitely for American poetry lovers and electric twilight tasters in which Buffalo Bill has died-, on the other hand, did not need a heroic fiction to tell his war - although it was also great-, nor nor throw or receive a single shot in the crotch (as it happened to the protagonist of Fiesta ). His scene of hardship was not a silver hill in the dark, under enemy shots, but a French concentration camp: his side, at last. His was a war of filth, of disease and filth, of a rotten and smiling despair; but also tragic, of reducing the body to its rubble and the spirit to ashes. Although, it seems, they could not with yours.

Just one year before Hemingway flew through the air and began to live, in his own flesh, what would then be his second novel, just one day after the United States took part in World War I, the Harvard graduate and Very young cartoonist and poet EE Cummings enlisted in the Norton-Harjes ambulance corps. During the boat trip he became friends with another American: William Slater Brown, named B in The Huge Room, the testimony novel - not self-fiction - in which Cummings realizes his seclusion in France.

As he himself recounts at the beginning quite gracefully - all the novel is tinged with a thin layer of irony, bright and cloudy at times, far removed from the usual grandiloquence of the war story - his superior, Anderson, was a type of the Bronx who I hated the French. Cummings and Brown -B- had several French friends and it seems that Anderson, A, as punishment, had sentenced them to perpetual cleaning of the ambulances. They protested more than once, something happened with a letter from B stopped in censorship, and the two friends were arrested. After a delirious journey of absurd interrogations, Cummings and B ended up in La Ferte-Macé, a detention center for those suspected of serving the enemy. As Cummings tells us, having a German father or reading Goethe were more than enough reasons. It was a disgusting place with damp walls, muddy floors, windows that let in frost, bedbugs, rashes, dirty water soups for breakfast and lugs in which they lived among their excrements. But his father, while on the other side of the ocean, was outraged by the lack of news of his son, whom he had left as a volunteer to fight against the Germans, but not against the French. Of course, nothing knew of his seclusion. He wrote to the American embassy in Paris and the State Department in Washington, but received no response . Desperate - because this intimate war, that of Cummings in France for his survival, was fought on these two fronts - he decided to write to President Wilson, as the father of an American son who had disappeared.

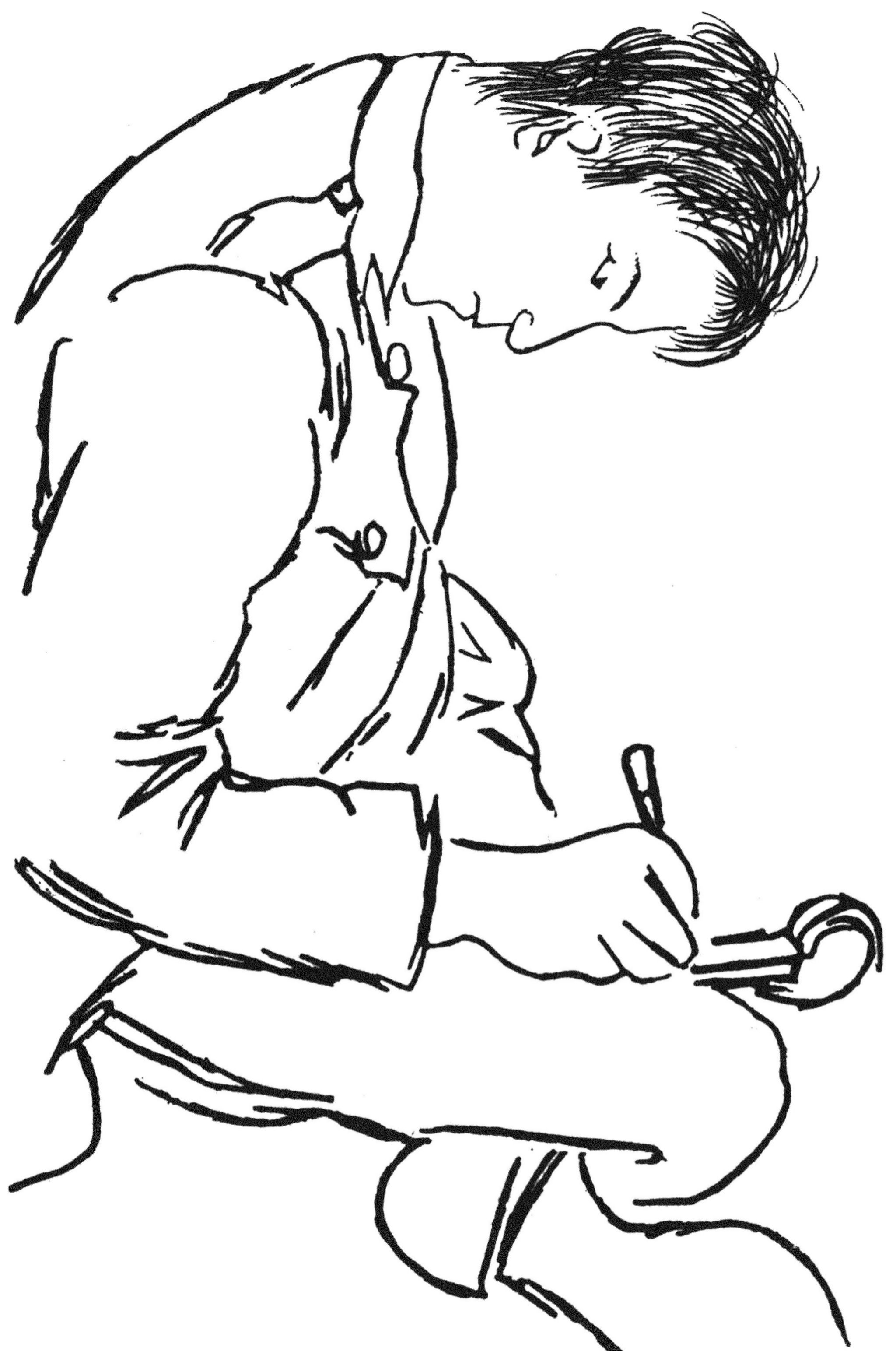

It was precisely his father, when Cummings finally returned home three months later, emaciated and malnourished, almost dead in life, who asked him to write what he had lived in France. And he did. Maybe that's why Francis Scott Fitzgerald, who stayed at the gates of embarking on Europe as an infantry lieutenant - although the war was waiting for him at home: he had just met Zelda Sayre - said years later that «Of all the works of young people who have appeared since 1920, there is a book that survives: The huge room of EE Cummings » . And he was right: because if there is a book that teaches us how to position ourselves against deprivation and horror, abuse and helplessness, but doing so with elegance and an inner humor that serves as a barrier or distance, we have it here. With the base of his drawn notes -reproduced in the excellent edition of Nocturna- and the impeccable poet's text with grace in the face of the desolation of his resistance - many died there, or were transferred to an even tougher prison, condemned to bureaucratic disappearance For his embassies-, Cummings details a microcosm of very hard, terrible conditions, in which dignity becomes a daily conquest.

In the huge room , any foreigner in France can be a spy. Also prostitutes, daughters and women of foreigners. This prison is a Babel of mud, dysentery and detritus: the smells become so thick that they can be cut with a bayonet. But despite the horror - and the stench - there is a fine beauty in his memory. Like when he tells us about the carnal Celina Teck, a worthy prisoner and presented as a Rita Hayworth more brunette, more panther or Carmen, or when she describes us to the Vagabond. Daily life and death, resistance and brilliance, with an aristocracy of living in the face of the grotesque arbitrariness of the French guardians with the real war at the back of the scene. A space without law, in full rearguard, but also with its own code, in which men and women will continue to look for their strand of splendor.

According to the criteria of The Trust Project

Know more- literature

- culture

The Paper SphereElizabeth Duval: "The mediocrity of certain Spanish intellectuals leads them to a transphobic language"

The Paper Sphere Antonio Pereira, the eagerness of every day and the job of telling it

Literature Brexit books: how the United Kingdom stopped being the best country in the world