- 'Blind sunflowers' and lost dignity

- 'The conspiracy of fools': tender awkwardness

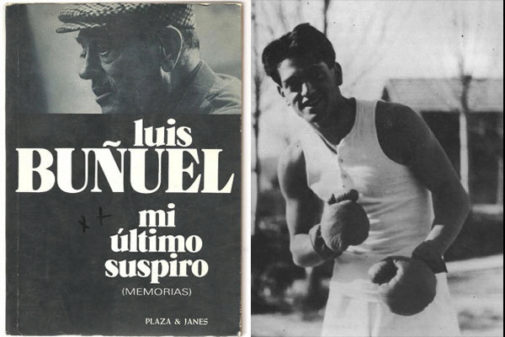

He had to be Luis Buñuel (1900-1983) a good guy, one of those with whom you would take a dry-martini to expect anecdotes with the whole day ahead. But not just any dry-martini, but a cocktail he invented, Buñueloni , "a simple plagiarism of the famous Negroni, but instead of mixing Campari with gin and sweet Cinzano, I put Carpano," he says in My Last Sigh ( Plaza & Janés, 1982). The ice had to be very hard, at least 20 degrees, so that it did not release water and with the same zeal, the filmmaker put drinks, gin and cocktail shakers in the fridge on the eve of the arrival of the guests. The ritual began by throwing on the ice "a few drops of Noille-Prat and half a teaspoon of coffee , of narrowness, I stir it well and throw the liquid, keeping only ...".

And already put, would tell that when he lived five months in the United States, in 1930, during the time of the Dry Law, he never drank so much; then whiskey was prescribed in the pharmacies, the wine was poured into the coffee cups, he knew places of the peephole and password and a trafficker who was missing three fingers of a hand taught him to distinguish true gin from counterfeit (" it was enough to shake the bottle in a special way: true gin made bubbles ").

And already put would continue to say that gin is "a good stimulant for the imagination", that it is impossible for him to drink without smoking, which began at 16 with cigarettes, which as an antidote to anguish in air travel followed the advice of a French magazine, take gin, and perfected it by pouring the liquid into a boot that covered with newspaper. And that he had two snacks a day, at noon and at six in the afternoon (he had dinner at seven) and that he soon went to bed.

Buñuel, if he liked you, could tell you about the adventures with Lorca by the Student Residence. "We were always together. He read divinely. He was brilliant, friendly. He made me discover poetry." And he would tell the night of 1924 when they went to the verbena of San Antonio and took a photo on a cardboard motorcycle and at three in the morning, both drunk , Federico wrote him a poem that he kept all his life.

Luis Buñuel would pout if asked about Picasso. They met at the end of the 20s in Paris and hardly dedicated a page of the book. "It was already famous and discussed. Despite its flatness and joviality, it seemed cold and self-centered ." And he tells an anecdote in which it does not turn out well, to finish off: "I don't like Guernica at all, although I helped to hang it. I dislike everything, both the grandiloquent bill of the work and politicization at all costs of the painting. I share this dislike of Alberti and José Bergamín, which I discovered recently. We would all like to fly the Guernica , but we are too old to ride bombs. "

Luis Buñuel Portolés was a child born in Calanda who very soon lived in Zaragoza, in a house with 10 balconies and five maids , went and returned in a horse carriage as a half-pensioner to the Jesuits ( Mass at seven thirty and Rosary for the afternoon ) and took violin lessons at age 13. And, as was necessary then, her virginity lost her in a brothel.

These memories of Buñuel (succulent, lavish in details) betray the author both for what counts and for what he forgets . No sign of egolatry when he won the Palme d'Or in Cannes in 1961 for Viridiana , the Golden Lion of Venice in 1967 for Belle de jour or the Oscar in 1973 for The discreet charm of the bourgeoisie . He does comment on the tribute that Georges Cukor urged and that he gathered at his home to (nothing less) Hitchcock, John Ford, William Wyler, Billy Wilder, Robert Wise ... But he only dedicates a page and a half. On the other hand, he stops at all kinds of abuses when he was part of that group of funny bandits who were called surrealists. Thanks to Man Ray and Louis Aragon seeing and getting excited with Un chien andalou (1929) he entered the fratry that met daily at the Cyrano café: André Breton, Max Ernst, Paul Eluard, Tristan Tzara, René Char, Magritte. .. "Everyone shook my hand." And he says it as if nothing. In passing, also, he comments that Un chien andalou was eight months on the bill, that Charles Chaplin saw her 10 times and that when he wanted to scare his daughter Geraldine he told her some of his scenes (confession made by his countryman Carlos Saura, who married was with her).

Just read the chapter For and against to know their mythomanias: I adored The 120 days of Sodom of the Marquis de Sade, the music of Wagner, the north and the cold, the noise of the rain ("now I hear it with a device, but it's not the same noise "), he could n't stand Borges (" I don't respect anyone because he's a good writer . I think he's quite presumptuous and self-worshiper "), he felt more than sympathy for Galdós (" often comparable to Dostoevsky "), Romanesque, Gothic and punctual art. And the first films of Fritz Lang: "they decided my life" . Not to mention weapons: "I have owned up to 65 revolvers and rifles, but I sold most of my collection in 1964, persuaded that I was going to die that year."

Thus ends the book, impeccable, disconcerting, like the previous 250 pages: "One thing I regret: not knowing what will happen. Leaving the world in full motion, like in the middle of a booklet. I believe that you are curious about what happen after death there was no yesteryear, or less so, in a world that hardly changed. One confession: despite my hatred of information, I would like to be able to get up from the dead every 10 years, get to a kiosk and buy several newspapers. I wouldn't ask for anything else . With my newspapers under my arm, pale, brushing the walls, I would go back to the cemetery and read the disasters of the world before going back to sleep, satisfied, in the tranquil refuge of the grave. "

According to the criteria of The Trust Project

Know more- culture

- literature

- movie theater

Culture Summer reading, music and cinema

The final interview Carlos Bardem: "Flags are rags that hide scoundrels and dirt"

The Paper Sphere Moby Dick, the obsession of revenge by Herman Melville