A group of scientists from Imperial College London (UK) investigated the rod-shaped bacteria Klebsiella pneumoniae. This bacterium, also known as Friedlander’s bacillus, is a dangerous nosocomial infection that infects the lungs and blood of immunocompromised patients. Microbiologists were able to determine the mechanism by which it became resistant to antibiotics. The results are published in the journal Nature Communications.

The resistance of antibiotic strains to infectious agents is particularly dangerous for hospital patients and is the result of natural selection through random mutations of bacteria when exposed to antibiotics. Microorganisms are able to transfer the genetic information of resistance to antibacterial drugs by horizontal gene transfer (when the transfer of the genetic code occurs directly between groups of living organisms, and not by inheritance, as during vertical transfer).

Like many other dangerous bacteria, Friedlander’s bacillus is becoming increasingly immune to the most effective antibiotics, including the class of carbapanem, used against a wide range of pathogens.

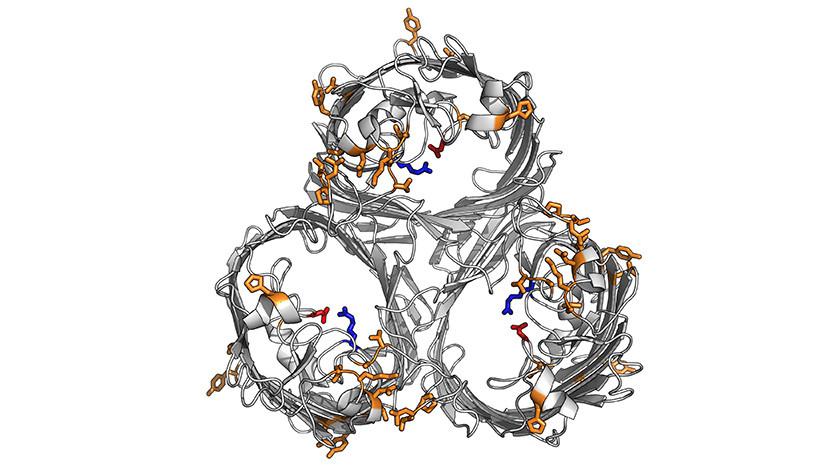

Scientists compared the structures of bacteria Klebsiella pneumoniae resistant and susceptible to carbapanem. In the structure of bacterial cells there are surface pores - a kind of door through which antibiotics enter the pathogen. In antibiotic-resistant samples, the researchers either found modified versions of the protein that forms the pores in the cell wall, or did not find such a protein at all. Modified resistant bacteria had smaller pores, which allowed them to "lock themselves" from antibiotic drugs.

- Structure of antibiotic-resistant protein of the bacterium Klebsiella pneumoniae

- © Wong et al. (2019)

After testing the bacteria in mice, it turned out that the "clogged" bacteria consume less nutrients. This leads to a slowdown in the growth of coccobacilli and weakens them, the researchers note. However, this does not fundamentally affect their antibiotic resistance.

Scientists are confident that their work will help in the development of drugs that can "open the locks" of bacteria.

“Since dangerous bacteria such as Klebsiella pneumoniae become resistant to carbapanem, it was important for us to understand how they succeed. This study provides us with extremely valuable knowledge that will allow us to develop new strategies and create new drugs, ”concludes study leader Joshua Wong.

Recall, the World Health Organization (WHO) considers the problem of resistance of bacteria to antibiotics one of the main threats to humanity. According to WHO estimates, about 70 thousand people die every year from drug-resistant strains of bacterial infections, AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. Experts warn that by 2050 this number may increase to 10 million.