John Elliott cannot be denied courage and courage: at his eighty-many years he has published what will undoubtedly be the most controversial work in his extensive bibliography, the book on Catalans and Scots (in the original English version The first word of the title is Scots, Scots; in the Spanish, the first is Catalan), an exercise in comparative history that, precisely because of its obvious virtues, will fully satisfy very few. Nationalism is a political conviction firmly anchored in the most emotional and irrational funds of the human soul, so any attempt to address its problems in an equitable and dispassionate spirit inevitably causes the angry rejection of one another. If it is also a study on two nationalisms, not one, and carried out by a British historian, English for more signs, whose specialty is Spain and, within it, Catalonia, crossfire will come from everywhere, despite the respect that Elliott's figure and work inspire, both in Britain and Spain and in the intellectual world in general. Sir John is a very experienced and sensible man, who will not be surprised at the criticisms or the silences with which his work is welcomed. It must be said that even the least favorable reviews express that respect I referred to earlier. What is quite surprising, however, is that the most hostile and worst-informed criticism of his book is published in the prestigious magazine where Elliott himself writes with some regularity (the New York Review of Books ) and is the work of a historian Scottish who has adopted the cause of Catalan separatism as his own.

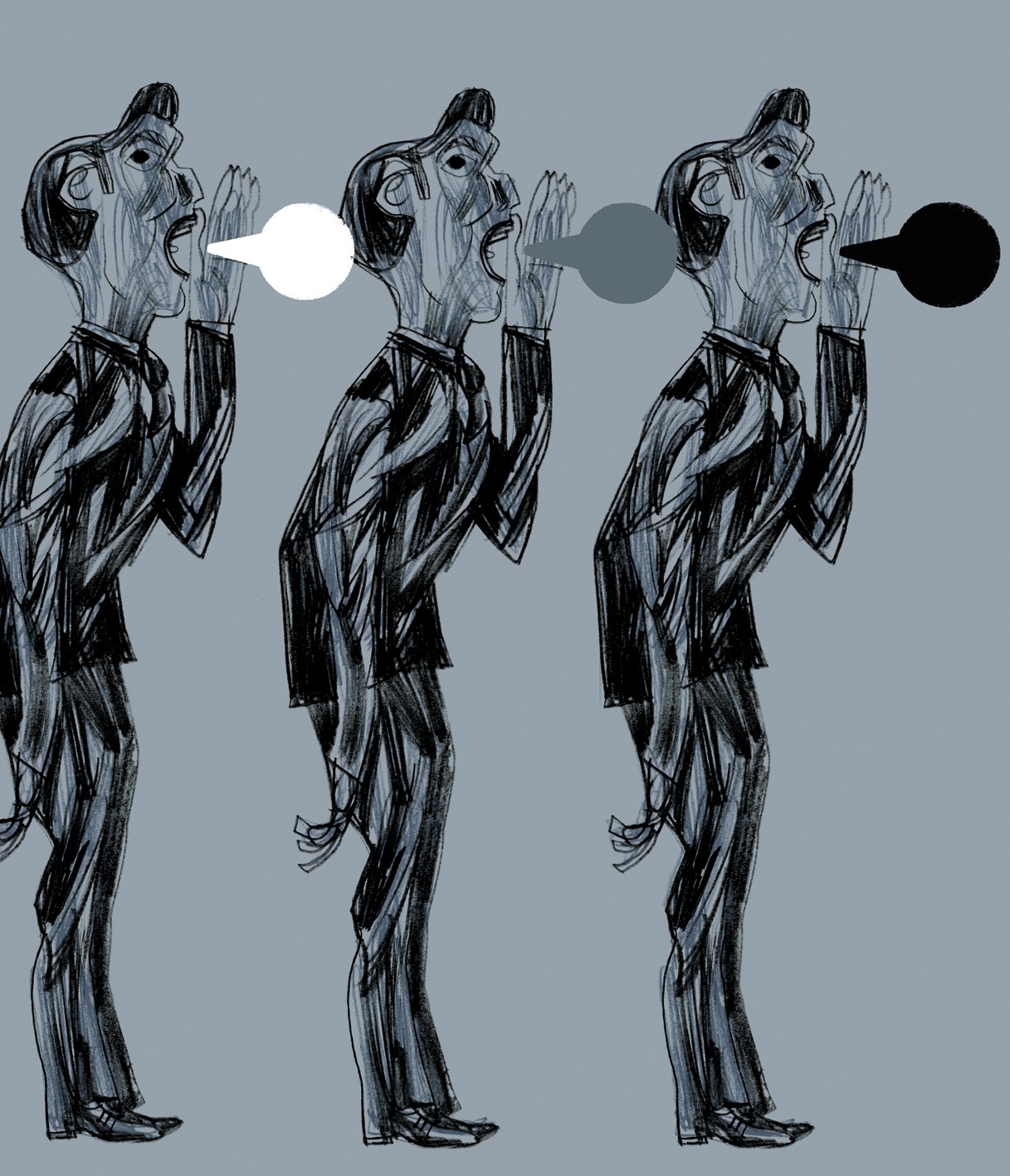

On page 255 of Scots and Catalans (I quote the original English version, which I read, but I translate the quotes from both Elliott and his reviewer, Neal Ascherson) into Spanish, Elliott refers to the television scenes on display throughout the world about the fray between police and protesters on the occasion of the October 1, 2017 referendum, and talks about the "bombardment of manipulated images and false information" that took place, including some "widely spread images of bloody voters [that actually] they came from other reports without any relation to the 2017 referendum. " And in this context, he adds: "The truth did not matter. Many foreign journalists, few of them well aware of the internal situation in Catalonia or the background of the secessionist movement, accepted without objection the images and stories circulated by the independentists." For Elliott's phrases apply perfectly to his reviewer, whose article in the New York Review of Books (April-May, 2019, pp. 33-36) is worth commenting, among other reasons because it demonstrates the international success he has had the propaganda of Catalan separatism, which has managed to wash the brain of this established British historian, among many others.

According to Ascherson, who begins his text with a panegyric by Clara Ponsatí that Juana de Arco wanted, the "rightist" Rajoy "panicked" before the illegal referendum "and behaved as if he were a king of the eighteenth century facing a armed rebellion. " These fragments already reveal to what extent the reviewer has endorsed the argument of the Catalan separatists . And it is curious to note that the Scottish professor argues with more energy against Elliott when dealing with Catalonia than when dealing with Scotland. Thus, he affirms that "Elliott's impartiality leaves him" when he addresses the current conflict and goes on to say that Philip VI's speech on October 3 was "for most of the rest of the world [...] a disastrous tirade and uncompromising [because] he did not even imply excuses or concessions. " One wonders by reading this to who has abandoned impartiality. It is very strange that a historian (and a British one especially) does not notice that a constitutional King cannot offer political concessions, and that he who asks for excuses because the Government had repressed a massive illegal and unconstitutional public act, organized by an autonomous Executive of a region that is part of Spain, would be totally out of place and would be humiliating for the Spanish State and people, apart from that it would produce a very serious confrontation between the Head of State and the Government. And, as a climax, Ascherson makes no reference to the two mass demonstrations against separatism and in support of the King that took place in Barcelona in the weeks following what he calls "disastrous diatribe" and which, according to Elliott (p. 255 ) was followed by "a resurgence of Spanish national sentiment throughout the country".

It is incomprehensible that the author of an article about a book like Elliott's shows such profound ignorance about the complexities of Spanish and Catalan history. Some errors are spectacular, such as when he informs the reader that Franco's rebellion took place in September 1936, which not only shows that he has not read anything about the Spanish Civil War, but that he has not read the book he is reviewing, which on page 215 correctly - and naturally - places the rebellion in July. The truth is that what Ascherson read from Elliott's book seems to have taken very little advantage of him. For example, this refers repeatedly to how very divided Catalan society has always been (or very often), referring to the peasant and urban wars of the 15th century, to the gut character that the Secession and Succession wars had, to the Carlist wars, etc. Ascherson does not seem to have heard and fully subscribes to the nationalist myths of a united Catalonia that speaks with one voice, which is precisely that of the separatists. Thus, he repeatedly refers to "the Catalans and their cause", their "constant victimization", the "struggle of the Catalans", as if that long half of those who resist the wind and the tide of separatism did not exist. The obfuscated Ascherson, of course, has not learned of its existence. Nor does he seem to know that the Catalans voted by overwhelming majority the Spanish Constitution of 1978, which today the separatists violate every day without the repressive Spanish Government doing anything to restore legality there.

Other bulk mistakes made by Ascherson include calling Barcelona "the last stronghold of the Republic" in the Civil War, as if Madrid, Valencia and Alicante had not resisted two more long months after the fall of Barcelona. He also erroneously states that the Tragic Week of 1909 was due to the attempt to introduce military service in Catalonia. He is wrong in almost a century. The Tragic Week began with a protest against sending troops to the war in Morocco. He also states, picturesquely, that being Catalan in Franco's time was "a clandestine identity." It is evident that Ascherson has forged a strange idea of Spain in general and Franco's Spain in particular, and that it should be recommended that he read again and with attention to Elliott; it would also be a good idea to look carefully at some history of Spain, of which there are many and good ones in English, before getting sick and sick in gardens that are unknown to him. And, if not, see the following pearl: he concludes by saying, referring to Spain, that "in Western Europe, a central authority that is only sustained through repression must change its behavior or perish." Not even Puigdemont would say it better .

As Elliott states, many poorly informed journalists spread false news about Spain and Catalonia. It hurts me that the New York Review , of which I have been a subscriber almost since its foundation, and that has been a model for so many other excellent publications, has declined so much since the death in 2017 of its legendary director Robert Silvers that, I am sure, I would not have missed the legion of historical rabbits that Ascherson has cast in this article. Subscribers in general, and John Elliott in particular, deserve better treatment. And he, of course, does not deserve this friendly fire.

Gabriel Tortella is an economist and historian. His latest books are Capitalism and Revolution and Catalonia in Spain (with JL García Ruiz, CE Núñez, and G. Quiroga), both edited by Gadir.

According to the criteria of The Trust Project

Know more- Spain

- Catalonia

- Barcelona

- Clara Ponsati

- Philip VI

- Madrid

- Mariano Rajoy

- Columnists

The Gang Walk Vacant Spain

Liberal Comments If we can yield

Letters to K. The dejected athlete