PEDRO CORRAL

Friday, March 5, 2021 - 3:45 PM

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Send by email

Comment

One night in 1938, during the Civil War, at the Military Hospital number 14 in Madrid, on calle de la Puebla 1, in the shadow of the Telefónica building.

A young nurse,

Teodora Palomo

, 22, crosses the deserted corridors.

Suddenly he meets a provisional medical captain,

Alfonso Fernández

, a 38-year-old from Tenerife.

She is startled and has reasons for it: the doctor is feared by all the companions as a stalker.

In fact, the medical captain rushes on her, grabs her tightly by the arms and tries to kiss her.

She resists, manages to disengage,

and flees with such anxiety that she is about to pass out from horror when she reaches her room.

The young nurse related this episode in her statement in a file for sexual harassment opened by the Republican authorities against Dr. Fernández.

And that is how a terrible story begins to be written, another one, of Madrid triply besieged by bombs, terror and hunger, which led to the intervention, an unusual case, first of the Republican Justice and then the Francoist Justice.

And the two agreed on the verdict, although not on the penalties.

The history in the middle of the war of that hospital number 14, located behind Madrid's Gran Vía, is preserved in the General and Historical Archive of Defense of Madrid, in the Francoist cause 1808, which in turn contains the republican cause 781. And In its nearly a

thousand pages

, from the abyss of a fratricidal war, the bowels of the human condition appear: death, pain, hatred, cruelty, betrayal, revenge, love, sex ...

"Nothing about a hospital, this was a Czech," whispers today one of the nuns of the convent, which is again that

Military Hospital No. 14,

since it was based in a monastery of Mercedarian mothers from the seventeenth century, who were evicted at the beginning of the war .

After this, the nuns returned in 1939, also restoring the church and the school, which continues to function today.

Jealous guardians of their convent, the nuns preferred to dismiss the request to visit their premises when we explained our purpose to write about the hospital that was installed there during the war.

Hence the phrase of the nun:

"From hospital nothing ...".

The truth is that a few days after the military coup of July 17, 1936, the Association of Dependents of Public Spectacles, of the UGT, seized the building to turn it into a "Residencia de Reposo" for the convalescence of wounded militiamen.

A young doctor from the same union was appointed as director,

Leopoldo Benito Fuertes, a

28-year-old from Madrid, also a doctor of the Provincial Charity, who is photographed in the courtyard, surrounded by ticket office clerks and ushers who acted as nurses, in a report on the residence published by the magazine

Now

on August 4, 1936.

In December 1936, after the battle of Madrid and the massacres of prisoners considered disaffected in Paracuellos, Aravaca and Torrejón,

the Republican military health service turned it into a hospital

to treat wounded prisoners of war, including Italian soldiers and German aviators;

convicted or prosecuted right-wingers who were ill;

and self-mutilated soldiers of the Republican Army itself.

A destiny that continues to be ironic for a convent of the Mercedarian order, dedicated to the redemption of captives.

A moment of lunch in the so-called Residencia de Reposo, in the same press report published in 1936. ALMAZÁN / 'AHORA' MAGAZINE / NATIONAL LIBRARY OF SPAIN

Dr. Benito Fuertes is confirmed as director, who goes from organizing a rest pavilion to governing a prison for wounded and sick enemies.

In addition to visible surveillance, with armed guards, another invisible one is established, with employees at the service of

the Military Information Service (SIM)

to detect and pursue, both among the detainees and among the personnel,

fifth columnists

or disaffected to the Republican side and also to the Communist Party.

The director, who will join the party in 1937, appears to be an active collaborator of the communist cell that poisoned the daily environment of the hospital with its power, not only relations with prisoners.

Suspicions, conspiracies and denunciations are growing among the employees, also fueled by resentments and personal envies, from which neither the director nor his lover,

the

20-year-old

nurse Prados Ramos García,

from La Mancha from Alcázar de San Juan, an affiliate UGT, whom many accuse of taking advantage of his love affair over Benito to make and break in a despotic way in the hospital.

The quarrels and discords end up exploding with the file that the director himself opens for theft and dishonest abuse against the medical captain Alfonso Fernández, the night robber of the nurse Teodora Palomo.

However,

the file turns against the director and his lover,

whom doctors, nurses and detainees denounce in their statements for carrying out or consenting to a series of humiliations and mistreatment of the prisoners.

Given the seriousness of the complaints, the Republican Military Health itself places the case in the hands of the Justice, dismisses Dr. Benito for lack of "moral authority" and decrees his unconditional imprisonment and prosecution together with Nurse Ramos, Dr. Fernández and the watchman

José de Santos.

More than twenty witnesses testify before the Republican military justice.

His most serious complaint is that

Prados Ramos injects gangrenous pus into the prisoners.

They also accuse Dr. Benito of passing away from his patients "without curing or treating them," and they point out that patients are held incommunicado for a long time and that one went crazy after eight months in isolation.

Dr. Benito and nurse Ramos deny the accusations

in the trial held in December in Madrid, at the Permanent Court of Military Justice.

Benito declares that the patient who ended up going mad was held incommunicado by the SIM, but that his ailments were treated.

He also states that he knew "by rumor" that Ramos spoke of injecting pus into a detainee.

The nurse asserts in her defense that it was "just a comment."

Despite these complaints, a report from the Military Health Headquarters praised the

"competent" professional performance of Dr. Benito,

certifying that between July 1937 and July 1938 the mortality rate in the hospital had been lower than in others: one total of 1,161 wounded and sick, 1,057 had been cured and only 23 had died, 1.98%.

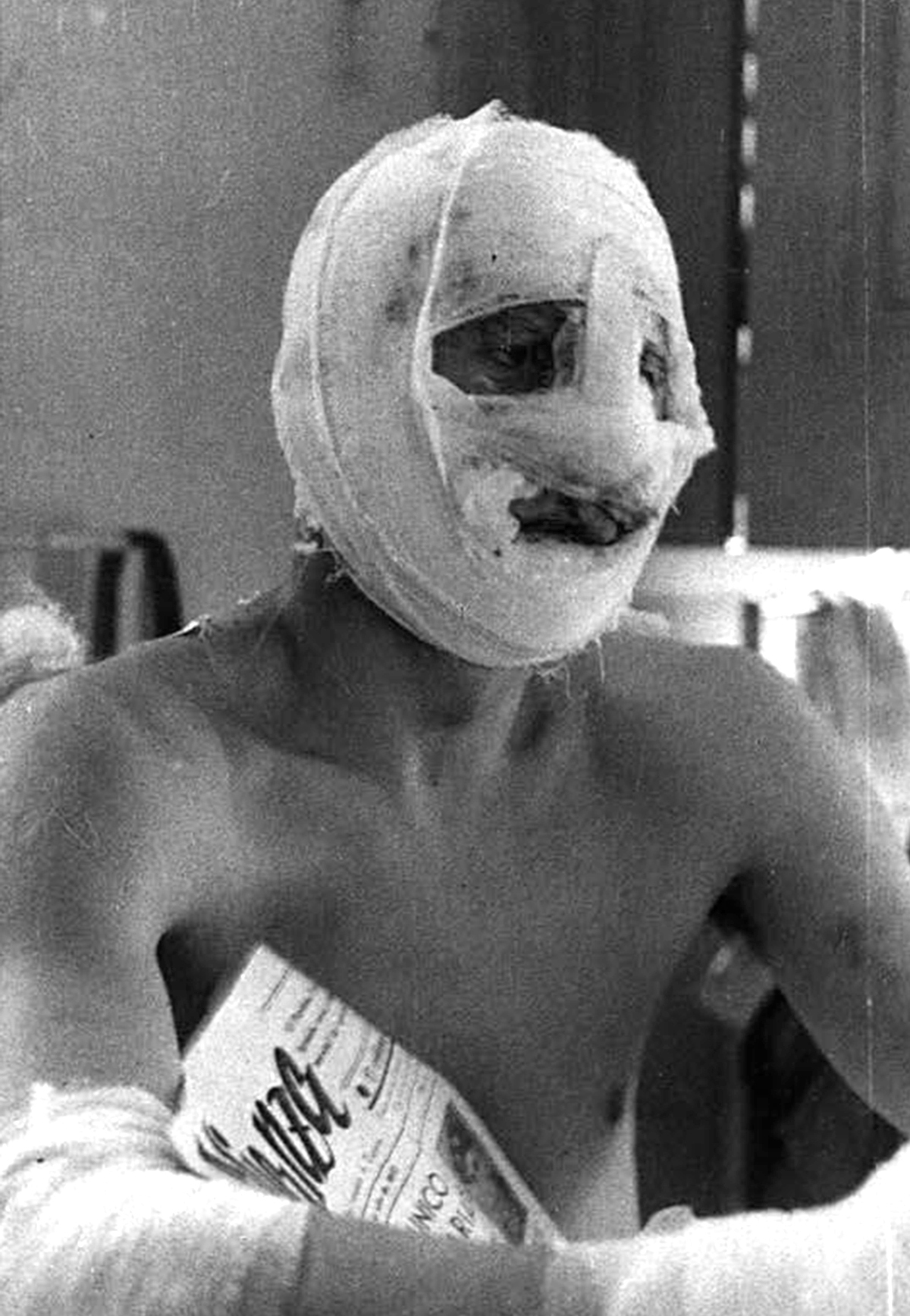

Photograph of the wounded German pilot Hans Seiter in the military hospital.

STATE ARCHIVES / MINISTRY OF CULTURE

The sentence established that nurse Prados Ramos proposed to another to

extract gangrenous pus from a

national

prisoner

whose leg had been amputated, in order to inject it into another tuberculosis detainee, "without the planned injection being given."

He also credited that "without being required by anyone or the state of the patient demanding it," he performed a "malevolent cure on a prisoner, with the intention of causing harm to the patient."

Likewise, it was considered proven that Dr. Benito punished

four detainees

for singing

Cara al sol

to be held for between two and three months, in winter, inside

a cell so flooded with fecal water and rain that they had to drain the mattresses

.

The director is held responsible for the "atmosphere of gossip, intrigue and partisanship" incompatible with a military establishment, to which "his love affairs with a subordinate" had collaborated.

Dr. Benito and nurse Ramos were sentenced by the Republican military justice to six years of internment in a labor camp for

"a consummate crime against the rights of nations,"

and the vigilante De Santos to three years as a collaborator.

Both the doctor and the guard had to serve their sentences in a disciplinary combat battalion for the duration of the war.

Benito was also sentenced to two years for negligence.

Dr. Fernández, tried for theft and dishonest abuse, was acquitted.

The imbalance between the proven facts and the harshness of the sentence against Dr. Benito and Nurse Ramos is still striking,

as if the court had wanted to punish more serious acts but without recognizing them

in the sentence, so as not to damage the image of the case republican.

Since June 1938, Dr.

Alejandro González de Canales,

who belonged to the clandestine Falange

, served as the new director of the prison hospital

.

His first decision was to move the hospital to a building in better condition, at Paseo del Cisne 6, now Calle Eduardo Dato.

Excerpt from the prosecution of the Republican Justice on the case.

GENERAL AND HISTORICAL DEFENSE ARCHIVE

The chaos at the end of the war allowed Leopoldo Benito and Prados Ramos to be released, although they were soon to be arrested again by the victors.

On April 1, the day Franco signed the last part of the war,

Jaime Benigno Soto,

50, who said he had been a doctor at Hospital No. 14,

appeared before Franco's police

to denounce Dr. Benito.

He accused him of treating prisoners "ruthlessly", and revealed that the Republicans had already convicted him of it.

The instructor of the new Franco case against the hospital-prison staff will come to recognize his "debt" to the republican process: "

So scandalous were the acts that were carried out in Hospital No. 14,

that it caused a process in the red era which serves as a precedent for the summary proceedings to which this qualification refers ”.

In fact, many witnesses of the republican cause returned to be it in the Francoist era.

Others now appeared among the

23 defendants, such

as nurse Elvira Navas, who had testified against Benito and Ramos, or Soto himself, who was arrested after reporting the events to the victors.

"SCIENTIFIC MURDERS"

New testimonies aggravated the accusations, even denouncing the commission of "scientific murders".

One detainee,

María Luisa López Ochoa

, 21, daughter of the general who put down the Asturias revolution, beheaded in July 1936 by a mob while sick at the Carabanchel military hospital, denounced that Dr. Benito operated on the prisoners "without anesthesia, saying that, as they were fascists, they had to endure.

Other testimonies reiterated the accusations against the director and the nurse for giving pus injections to a veterinary commander,

Joaquín López López,

an ensign named Giménez and an Italian officer arrested in Guadalajara, in some cases mixing the pus with turpentine.

Benito presented a brief denying the injections of pus and alleging that inoculating the essence of turpentine, a component of turpentine, was a treatment for infections, which is true: it was called a

"fixation abscess"

, common before the discovery of antibiotics.

Dr. Benito was also accused of letting a

national

prisoner

wounded in Brunete

die without any cure

, who died with his hands and feet tied.

One detainee declared that he asked for insulin because he was diabetic and told him that "what he needed was four shots like all fascists."

Another prisoner,

Carmen de Blas,

28, said that she was locked up in an isolation cell despite being pregnant and that the director made her the object of "endless ridicule" depriving her "even of the most essential."

Current view of the building, which today is a convent.

The one who would be the second director of the center, Alejandro González de Canales, acknowledged that the prisoners were mistreated, who were told

"not to complain too much because they all had to be shot."

He denied that Benito was abusing himself personally, although he "encouraged" them, or that he was given injections of pus and operated without anesthesia.

Another doctor,

Honorato Pérez,

said that the hospital was "a true Czech" and that "the director, more than a doctor, was a hit man."

Regarding Jaime Benigno Soto, appointed provisional medical captain by the Republican Government in October 1937, Dr.

José María Rubio

revealed that "he passed as a doctor not being one" and that, in reality, he was a hotel concierge.

Soto himself, who lost his eldest son, Benigno, commander in the 43rd Republican Division, in the battle of the Ebro, confessed never having practiced the profession, although he finished his medical studies in Santiago de Compostela in 1914.

A nurse stated that "once he did not know how to tie an artery, causing the patient to bleed and having to call another doctor", although she did not know if he did it "due to ineptitude or malice."

Another assured that, seeing a prisoner bleed to death, Soto ordered that

"they leave him because losing blue blood, they raised it red."

However,

there were detainees and prisoners of war who presented guarantees in favor of Dr. Benito,

acknowledging his good treatment.

Several testimonies confirmed that Benito certified false illnesses or uselessness for not serving in the Popular Army.

Even a witness to the republican process declared to the Francoists that he had then exaggerated the accusations against Dr. Benito so that he would be relieved by a doctor from "the fifth column", as indeed it happened, although he later rejected this statement.

The sentence, handed down on June 6, 1940, was unforgiving.

Of the 23 defendants, seven were sentenced to death for

"adhering to the rebellion":

Dr. Leopoldo Benito Fuertes, Jaime Benigno Soto Liberia, the nurses Prados Ramos García, Elvira Navas Traverso and Joaquina Rodríguez del Amo, and the guards Francisco Vaquero Hernández and Eusebio Impuesto Álvarez.

Dr. Alfonso Fernández Hernández was sentenced to 12 years and one day in jail.

Defendants and accusers in this double republican and Franco process were

shot on June 27, 1940 in the Almudena cemetery,

although a vile stick was requested for Benito and Ramos for "the perversity" of their actions.

Until his execution, Dr. Benito treated the Republicans imprisoned with him in the

Porlier prison

as a doctor, with "very good conduct"

.

This was recognized by the director of the prison.

According to the criteria of The Trust Project

Know more

See links of interest

2021 business calendar

Zenit Saint Petersburg - Real Madrid

West Bromwich Albion - Everton

Maccabi Fox Tel Aviv - Valencia Basket

Parma - Internazionale

Levante - Athletic, live